In his comment on Part 2, Dave wrote, “I can’t imagine what your arms feel like after all those cobbles!” On the cobbled climbs, actually, it was all about the legs and the lungs.

When Anita and I talked about our rides in January, she talked exclusively about needing strong legs and endurance. At some point, it occurred to me to ask, “You never did any flat cobbled sections did you?” Anita had no idea what I was talking about. So as Rachel planned our Return to Flanders, I insisted that Anita had to experience something very special from my ride in January.

The Mariaborrestraat is almost entirely flat. On a map, it looks like an indirect way to get from the Koppenberg to the Taaienberg.

The Mariaborrestraat is also a cobbled road in very bad condition. After my experience in January, I wanted Anita to see what cobbles could be like, at speed. Here’s the beginning of the stretch; the sign reads “Pavement in poor condition” which is a bit of an understatement. (In Luxembourgish, the equivalent for “slechte” also means “drunk” — make of that what you will.)

Here’s what Anita wrote to me about it:

This is the section that you REALLY wanted Rachel and me to do, and now I know why. Oh. My. God. It was painful and terrifying and amazing all at the same time. You must have benefited some from your mountain biking experience. I just was scared out of my mind all the way through the 2.4 kilometers. At any point, I could have easily gone down. I was just bouncing all over the place.

Excellent… Mission accomplished.

I gave Anita some “mountain biking” advice before we hit the straat: sit up and out of the saddle and use your legs as shock absorbers. I’ll admit now that I didn’t give very good advice. The rear end of a road bike is so light that getting out of the saddle allows it to bounce all over the place. I shifted my weight forward, so that I didn’t care that the rear wheel had almost no traction. Anita chose to sit back down, regain control… and suffer the consequences.

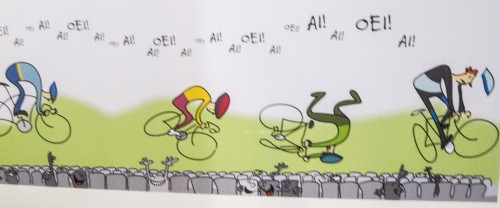

The Ronde museum portrays it in an image:

Yep, that’s about it.

There are two amazing things about cobbles on the flat. One is that there’s a magical speed for any stretch of cobbles, where you hit each one just right and float across the tops. That speed is always changing, so you feel it once or twice for a few seconds. That feeling compels you to vary your speed constantly, hoping to find that place again.

The second is a kind of corollary: there is no speed, no path, and no grip that will keep your arms from feeling like you’re being electrocuted. If you hold the handlebars lightly, they slam into your palms and you risk losing control. If you squeeze the handlebars, you will loose sensation almost immediately from your fingertips to your shoulders.

As an occasionally haphazard wannabe electrician, I know what it feels like to grab a live wire. I’ve never felt anything as much like it as riding fast over cobbles while clenching road-bike handlebars.

For fans of pro cycling, the ultimate and legendary course for flat cobbles is the Paris-Roubaix. Everyone says that the cobbles there are worse in every way. I must have a little bit of Anita’s masochistic streak, because I’m curious and wouldn’t mind checking it out.

The best part of the Mariaborrestraat left all three of us gasping for breath. We were struggling up a little incline all together, and an elderly woman dressed in casual clothes and easily pedaling her heavy cruiser-style bike zoomed past us without warning. We shared an instant reaction: What the heck!?!! We knew that people living around here would be tougher than most, but that was preposterous! Within a few seconds, she turned off the road; then we saw the small battery pack between her legs. And started laughing.

The next climb arrived all too soon: the Taaienberg. I don’t have a good photo of the climb itself, but it’s a shaded climb that seems like a slightly easier version of the Koppenberg. It’s a bit longer, but it is also a bit less steep overall and at its maximum grade.

I guess I’ll need to go back again soon to document the Taaienberg properly!

Anita and I simply were not ready for this climb. I don’t know whether more time to recover would have made any difference. The overhanging trees, the shade, and the runoff from the soil embankment meant that the cobbles were still slick, even at midday. And yet that’s no excuse…

…because there is a concrete verge along the entire length. (Watch the cyclists move to the right in this video.) Despite that advantage, Anita and I both came to a shuddering halt less than half-way up.

After walking for a few dozen meters, Anita made a compelling case that the concrete gutter would make it possible to get on the bike again. We strained our legs again and slowly caught up with Rachel, who was waiting on the open, flat section at the top of the hill. She was ready to go, but I demanded a nice long break in the sun. It was just cool enough that we didn’t look for shade. I took some photos, of course.

After the Taaienberg, we had a respite from cobbles. We were high atop a ridge, cycling alongside woods on high-quality surfaces. It looked and felt a lot like cycling in Luxembourg.

We knew we’d made it through all but one of the named climbs. We relaxed, riding three abreast and chatting. There was no need for a Plan B anymore, and Anita and I could stop wondering whether we’d make it all the way through our planned 60 kilometer ride.

The last climb, the Kruisberg, passed through the large town of Ronse. It was disorienting to descend straight into traffic and storefronts, and we wound up climbing halfway up the non-cobbled climb on a parallel street.

Apparently, that easy prelude was a good warmup for the real thing. All three of us pedaled up the climb without much trouble. The cobbles were slightly smoother, and the maximum grade was 9%. As Anita said, “The Kruisberg showed me that anything above a max incline of 11% on cobbles is a bit out of my grasp right now.”

After the Kruisberg, we continued to grind uphill in fast traffic until we were atop the ridge again. Then it was a smooth, fast descent to the bike-path along the Scheldt. There, we found that Flanders had one more challenge for us: a strong headwind for the last 10 kilometers home. Anita and I were shameless about drafting behind Rachel. Even with that advantage, we were getting slower and slower. Then I discovered that two lead cyclists, closely side-by-side, almost negated the wind. Anita and I took turns sheltering each other while Rachel generously remained the stalwart windbreak.

When we saw the lift bridge of Oudenaarde, we could finally celebrate our accomplishment. What better way than an adult beverage on a sunny terrace?

When we saw the lift bridge of Oudenaarde, we could finally celebrate our accomplishment. What better way than an adult beverage on a sunny terrace?

An adult beverage and a tiny friend, that’s what!

We stayed in Oudenaarde overnight, enjoying take-out pizza from the very good Italian restaurant (Arcobaleno) next door.

Anita and I had planned to visit World War One sites like Ypres the next day. We stayed in Oudenaarde due to the combination of a beautifully sunny morning, sore legs, and the desire to relish our ride for a few hours more.

Anita and I had planned to visit World War One sites like Ypres the next day. We stayed in Oudenaarde due to the combination of a beautifully sunny morning, sore legs, and the desire to relish our ride for a few hours more.

You won’t be surprised to hear that our Flemish ride became the touchstone for the rest of this year. Every climb in Luxembourg is compared to the Oude Kwaremont or the Kruisberg. It is now imperative that we look up the percentage grade of the climbs around our home. We seek out the cobbles in Bourglinster and the Ville, and then scoff at how smooth and easy they are.

I’m afraid we are becoming insufferable. Perhaps we need another dose of humility… and I know where to find it…

2 Comments to “Return to Flanders, Part 3”

3 July 2014

And to think, the biggest climb I’ve done this year is a 2.0% grade….

4 July 2014

Hey, Dave, there’s a 2% rise just outside of town that destroys me every time. It just goes on and on, and if I don’t look at my speedometer, I think I’m doing great. If I do watch it, I notice that I’m consistently dropping speed. And if I’m with others, it’s where I drop off the back and then, no matter how hard I go, I can’t seem to make up ground.

Beware the 2% grade!